What CMS's VBID Termination Might Mean for Food as Medicine

Along With a Recipe That's Wiser Than Most

Note to readers: I can’t thank you enough for being here! If you like what you’re reading, please share, like, or make a comment down below. Your engagement makes all the difference in growing this newsletter.

Whether you are a healthcare or food industry stakeholder - be it a startup, community-based organization, VC, health plan, consultant, dietitian, farmer - or a consumer, the words I write here are for you.

This is not medical advice.

Value-Based Insurance Design - The Risk Score Paradox

What happens when healthcare policy moves faster than evidence?

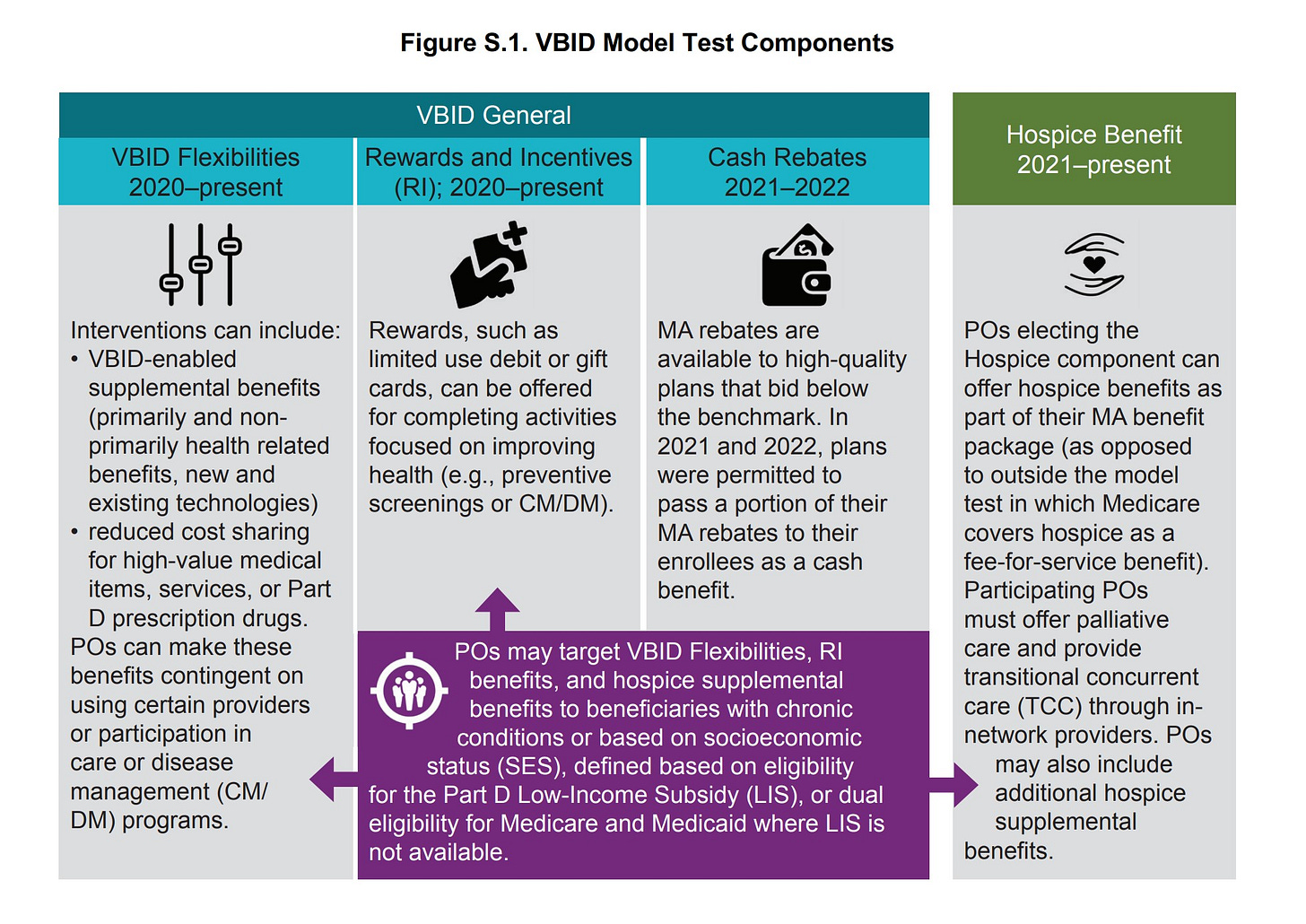

This month, CMS announced the end of its Medicare Advantage Value-Based Insurance Design Model (VBID) — a program allowing Medicare Advantage plans to test an array of interventions aimed at improving health while lowering costs. The model was straightforward: provide beneficiaries with reduced cost sharing, supplemental benefits, and/or rewards based on chronic conditions and/or socioeconomic status to mitigate costlier health services down the line. Remove barriers to preventive care, and both patients and their respective plans would benefit from improved health outcomes.

So what went wrong? It turns out that the VBID Model resulted in the opposite of what it intended — an increase rather than a decrease in risk scores and therefore, more dollars CMS will need to pay to participating health plans to meet the needs of their now, riskier beneficiaries.

There are a few dynamics to consider and further explore. Did beneficiary health actually decline as a result of program participation? This seems unlikely given the focus on preventive services, though it raises a critical point — the health impact of interventions within our current healthcare system should be better understood. Or, did participants' health improve (or remain stable), but appear worse due to an increase of documentation of existing conditions? Ultimately, the program's fate was sealed by the rise in risk scores, a direct contradiction to the program's health improvement/cost-reduction aims.

I can’t go on too much of a tangent — you can see just how tempting it can be —since my focus is on Food as Medicine/Health, but the end of CMS’ VBID program raises a few thoughts/questions to consider for the healthcare system we are trying to integrate food and/or technology into.

Does an increase in healthcare utilization lead to ill health?

This example is far from perfect but let’s explore a somewhat controversial scenario for just a moment.

If I were to receive a $100 voucher for fresh produce as a reward for attending my annual doctor’s visit, I would have otherwise avoided, and it was discovered that I had anxiety, would I be better or worse off in both the near and far term if I were to recieve a medication as a result? I’m not questioning the intent of my hypothetical doctor, but rather the very nature of our healthcare system which is geared toward intervening vs. not. I am now a “riskier” patient who might become even riskier due to potential side effects and/or any other complications that might stem from perhaps a more holistic approach that would address the root cause of my anxiety.

Now, let’s say I received a referral to a mental health provider in conjunction with or in substitution of a prescription — I still might be deemed a “riskier” patient, but aren’t I healthier in both the near and far term?

So in the case of the second cohort (the group that did not participate in CMS’ VBID model) in the best-case scenario — that increased health utilization doesn’t lead to worse health outcomes — aren’t we just delaying greater costs that must be paid at some point down the line?

Any way you look at it, one thing is clear: our U.S. healthcare system is broken. While food/nutrition support was just one component of the VBID Model (and I have yet to find a report that isolated the positive or negative impact of this specific intervention) the program's premature end has implications for Food as Medicine moving forward. The good news is perhaps we can learn from the fundamental flaws in how we implement and evaluate preventive, holistic care interventions, but we need to be able to have difficult conversations around healthcare delivery before the substantial progress we so desperately need can be made.

Food as Medicine Going Beyond Pilot Programs

Last week I scratched the surface on the limitations of Food as Medicine delivery via ILOS and Section 1115 Waivers, highlighting three critical challenges: they're temporary by design, creating an inherent barrier to broader adoption; they lack quality metrics based on rigorous research, and health outcomes measurement, creating confusion around their true value and therefore impeding waiver renewal and new state approvals; and their severely limited reach, due to the very nature of a pilot. With only a handful of those who stand to benefit from Food as Medicine interventions (and the preceding metabolic disease reversal that these interventions should be geared toward — I’ll get to this point soon), Food as Medicine faces an uphill battle within the current structure of our healthcare system.

While Medicaid waivers have been instrumental in advancing Food as Medicine, they're just one path forward. Private insurers aren’t as constrained to operate solely within the bounds of Medicaid and therefore, have more freedom in how food/health tech interventions are incorporated within their care delivery. Value-based payment models offer perhaps the most promising avenue, though their funding structure is complex and multilayered: health technology and food delivery companies provide programs with payment contingent on results, while insurers can earn rewards from CMS based on improved health outcomes. Yet this seemingly elegant solution faces real hurdles, particularly in structuring risk-sharing agreements between parties and establishing clear causal links between food interventions and health improvements.

The Promise of Value-Based Care?

What changes are needed for Food as Medicine programs to integrate seamlessly with (i.e., can plug right into) a value-based arrangement? This question becomes particularly critical given CMS's goal to enroll all Medicare beneficiaries in Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) by 2030.

Curious about Food is Medicine / Food is Health?

Subscribe to The Savory for:

Detailed breakdowns of Food as Medicine programs, including payment pathway evolution, implementation barriers, and success stories

Inside looks at organizations pioneering Food as Health, featuring conversations with leaders driving metabolic disease reversal at both the systems and clinical levels.

Reason being: CMS’ innovation strategy to transition Fee-For-Service beneficiaries into ACOs has become synonymous with VBC in the context of Food as Medicine/Health delivery. The reason for the nuance isn’t meant to be provocative but rather, to initiate a conversation that might proactively alter the path forward for food/health tech being used as a tool within our healthcare system for metabolic disease reversal. We'll unpack these system-level challenges in a later post. For now, let's focus on what VBID's termination might mean for the space.

CMS’ VBID Model allowed Medicare Advantage plans to test interventions aimed at increasing access to and uptake of proactive services that would improve health and lead to lower utilization of costly services down the line.

Participating organizations (of which there were 62, serving over seven million enrollees) offered a variety of services and incentives to increase beneficiary engagement. Such interventions were geared toward 1. utilizing high-value treatments, services, and providers; 2. cost-sharing reductions for beneficiaries, and 3. programs promoting healthy behavior.1 A most simplistic example is free transportation to a routine appointment in combination with generic drug coverage (zero cost to the enrollee), which, in its absence, might otherwise result in an emergency event.

However, CMS terminated the program due to an unexpected result — high cost and an increase in risk scores (which leads to further costs). In other words, the efforts that Medicare Advantage Plans took to remove obstacles to health and health care resulted in a higher-risk, “less healthy” population than if there had been no early interventions or nudges to promote good health.

Initial findings from the 2023 evaluation of the VBID model indicated that the model incurred substantial costs in part due to the fact that risk scores of enrollees in MA plans participating in VBID increased substantially more than those of similar enrollees in other MA plans not participating in the VBID model. - CMS’ Evaluation Findings and Model Termination

The model's termination raises three critical questions.

First: aren’t we just falling into the trap of having to pay more for services later down the line? Although we have the non-intervention cohort (i.e., beneficiaries whose plans did not participate in the VBID Model) as a comparator, we don’t have the long-term cost savings/expenditures and associated health outcomes of this cohort.

The second (perhaps most solemn perspective): Did higher utilization/medical touchpoints lead to new diagnoses/conditions reported (what contributes to a higher risk score) without any meaningful change in outcomes — and if so, did we accomplish anything within the VBID Model?

Or, (question #3): did these services lead to an increase in healthcare utilization that might not have resulted in improved health outcomes since we haven’t fundamentally altered the treatment landscape for the comorbidities stemming from metabolic dysfunction?

What does this mean for Food as Medicine?

It means that any program under the VBID model, including nutrition support, might face heightened scrutiny.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Savory to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.